Google Earth’s Virtual Globe

Since its launch in June 2005 Google Earth has attracted not only the millions of people across the world who fly virtually across continents and jump over mountains, but has also fascinated the geography, geomatics and environmental-sciences community. These professionals have been following developments with extraordinary attention, their comments often worded to express excess: ‘astonishing’, ‘fantastic’ and ‘exciting’. Why are so many people enthused by the Google Earth phenomenon when it is not the only Virtual Globe, and not even the first one? Skyline Software Systems is one of the first companies that produced a Virtual Globe, calling it TerraExplorer. Another free Virtual Globe is NASA’s World Wind.

Data Explosion

The difference is all about business models. Google’s basic mission is to sell ads for display on internet-accessible platforms. As such, it has with Google Earth created a tool easily accessible to the casual user: the father wanting to plan a family holiday and the businessman to book a hotel. And it is an extremely user-friendly tool; anybody with just basic computer skills can use it. On the other hand, TerraExplorer focuses on the professional user, whilst World Wind is designed for processing and analysing scientific data; its code is open-source, so that scientists and software developers can carry out modifications depending on their needs. World Wind is slower than Google Earth and uses much more computer resources in terms of storage place and computation time. Google Earth overcomes the data-explosion problem by using a tiling structure that transfers increasingly higher-resolution data when zooming in. How the tiling structure works can be studied thoroughly when using a very slow internet connection. Further, data-compression techniques and other clever computer engineering methods largely diminish file size. With broadband connection, data transfer and display are performed virtually in real time.

Developing Countries

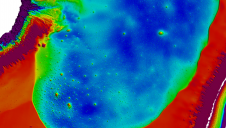

A Virtual Globe allows you to discover the world from your armchair. The background data in the Google Earth model basically consists of airborne and space-borne images, not all of recent date: some may be up to three years old. The literally hundreds of thousands of individual images are derived from over a hundred sources, including Landsat satellite, DigitalGlobe’s Quickbird and many providers of aerial photographs. They are glued together so that the user can fly over the world and change altitude like supermen in science-fiction stories with just a movement of the mouse button. Starting from an orbital view of the Earth, one can zoom down from space right to the place of interest; where image resolution allows, even to street level to observe individual cars and identify people. The mosaicking of images has not always been carried out perfectly, as I discovered when I zoomed in to my own house. The street suddenly ends in front of my house because of a shift of about 10 metres between two images.

Some cities, such as Los Angeles, are represented in three full spatial dimensions. However, other parts of the world, in particular the developing countries, have to make do with 15-metre resolution imagery as provided by Landsat TM. By choice, just by ticking, one can add to the image, view road-maps, territory boundaries and layers containing information on lodging, dining, shopping, and even on pharmacies and grocery shops. Zooming in on Africa, one frequently encounters deformed red crosses, at first glance seeming to identify forbidden zones but on closer examination seen to represent aeroplane icons; zooming in discloses an aerial image overlay on top of the Landsat TM background image showing the area in detail. Every view shows one, two, and sometimes even three copyright references. This may give a clue as to how much organisation and negotiation it must have taken to make all this data accessible from one browser.

GIS Democratisation

The scientific journal Nature has recently devoted several features to the Google Earth phenomenon, quoting such geomatics celebrities as Prof. Michael Goodchild from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Jack Dangermond, founder and president of ESRI (Nature 439, 16th February 2006). Goodchild is convinced that tools like Google Earth will increase awareness of the potential of GIS: “It is like the effect of the personal computer in the 1970s, where previously there was quite an élite population of computer users,” he says. “Just as the PC democratised computing, so systems like Google Earth will democratise GIS.” According to Dangermond, ESRI is reacting to the vigour of Google Earth by this year releasing a large upgrade of ArcGIS which enables users to publish virtual globes on the internet and analyse their own data in whatever format, so long as it is compliant with OGC specifications. For this several thousand functions are arranged within an internet environment. In addition, ESRI will release ArcGis Explorer, like Google Earth a free visualisation tool.

For more consideration of Google Earth, see the feature by contributing editor Arie Duindam. For more information on today’s satellite images consult the Product Survey. To download the free version of Google Earth is very simple. Just go to www.google.com and search for Google Earth and with the first hit you arrive at the Google Earth site, then follow the download instructions.

If you have not done so before, just do it, and be amazed!

Value staying current with geomatics?

Stay on the map with our expertly curated newsletters.

We provide educational insights, industry updates, and inspiring stories to help you learn, grow, and reach your full potential in your field. Don't miss out - subscribe today and ensure you're always informed, educated, and inspired.

Choose your newsletter(s)